#246: The Case For Prioritizing Physical Literacy In Youth Sport.

Youth sport may provide the only physical activity some kids get, should that change its purpose?

Recently, in discussion with a local strength and conditioning coach who works with elite athletes, he mentioned the wear and tear he sees. Pro athletes in their early twenties are coming to him in the offseason with knees and hips that function like they are 50 years old. In sports like hockey, the year-round focus on skating without a counter balance, the body breaks down after 10-12 years regardless of age. More and more athletes he sees in the offseason require remedial and therapeutic work over 3-4 months just to get them close to being a full capacity. Some required 6 months or a year of rehabilitation, but can not afford to take the time off. This is setting our young athlete up for difficulty physically, especially post career. They spend their entire life rising to the pro level, only to have their body break down during their earning years. Without proper care, their performance compromised, their career cut short and perhaps most importantly a life beyond their pro career in pain and discomfort.

That is 1 extreme of movement capacity, a component of physical literacy, not being balanced. The overuse extreme.

While this is an alarming trend, it affects a very small percentage of the population. Those who are peaking and pushing into pro level in the 18-30 years old age bracket does not represent the majority.

The more common example of poor physical literacy is the other extreme.

Those youth under 18 who are not getting enough activity represent the majority. The repercussions of not getting enough activity also impacting health in later life to the pro athlete, even though the root cause is very different.

TPM has documented how the lack of activity also impacts health during youth.

The lack of activity diminishes the quality of the youth sport experience itself. If a young person does not move well, or have the capacity to meet the demands of the activity then the sport experience will not be fun. Period.

Unfortunately, this last part is more and more prevalent in my experience coaching. In the last 20-25 years the changes in our youth’s ability to move is eye opening.

Basic movement skills such as running, turning, speeding up, slowing down, jumping, skipping, anything involving weight transfer (which is everything in movement) have all declined. The major reason: there are less and less opportunities for our youth to move.

Globally, 80% of adolescents are insufficiently active, and many engage in multiple hours of daily recreational screen time.( Source: National Library of Medicine).

There is very little recreational play outside in our youth today in the western world. Regular, daily physical education has been removed from most of our schools. What does this leave as an outlet for physical literacy development?

The focus of youth sport is not necessarily physical literacy is it?

In edition #245 of The Physical Movement, we covered the importance of clear vision and mission statements in youth sport.

In edition #246, we ask, should those statements include the mandate to develop physical literacy?

Let’s dig in a bit.

First, what is physical literacy?

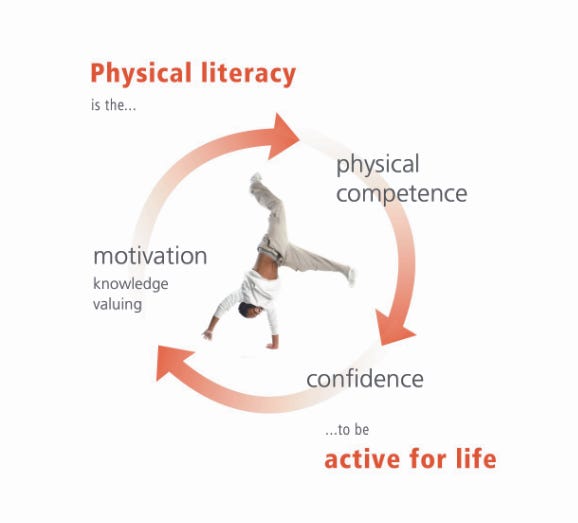

“Physical literacy is the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life.”

– The International Physical Literacy Association.

In short, physical literacy is a skill that covers physical, cognitive and behavioral components tied together by the motivation and confidence to be active throughout life.

Second, should physical literacy be a mandate for youth sport to prioritize?

At first glance, the driving components to developing physical literacy are the focus on physical competence in addition to knowledge.

Physical competence refers to an individual’s ability to develop movement skills and patterns, and the capacity to experience a variety of movement intensities and durations. Enhanced physical competence enables an individual to participate in a wide range of physical activities and settings.

Knowledge and understanding include the ability to identify and express the essential qualities that influence movement, understand the health benefits of an active lifestyle, and appreciate appropriate safety features associated with physical activity in a variety of settings and physical environments.

With strong physical competence as well knowledge and understanding, our youth build their confidence, self-esteem grows and positive lifestyle decisions are made.

Without these skills, well, we see what we see today. 80% of our youth who do not get the required amount of activity.

This is all well and good, but is it realistic to be asking our youth sports programs to do more?

The realistic perspective is that prioritizing physical literacy is not asking YSO to do more, but to assist with a different set of skills. Years ago, the foundational skills in sport were to teach our youth sport skills. Fielding a ground ball, throwing and kicking accurately, base running, skating skills etc.

What happens if our youth cannot run well? Or, have very little balance when on skates, or can’t coordinate the movements to throw or kick or handle a ball?

A step backward to a lower baseline is now the current starting point.

Development of balance, coordination, reaction time, speed, power, and agility are the skill components of fitness, and are required in order to develop the sport specific skills.

Skill components of fitness are the backbone to physical competence.

They must be in place before sport specific skills can start to develop.

By starting with skill components of fitness, the foundation is set for sport specific skills.

Every coach’s certification should cover a module on how to teach the skills of fitness from a young age. Drills and exercises that can be taught from a very young age and reinforced all through youth sport.

The reality is once the skill components of fitness are developed, they become warm up steps for those that are more advanced. Practicing them never go away.

If youth sport wants to make the biggest impact, prioritizing and developing the skill components of fitness become the new starting point in towards strong physical literacy and most importantly healthier and better prepared younger generation.

another coach provided the below feedback. Coach Phil Campbell has some great feedback for hockey/skating athletes around their hamstrings tightness. Many youth coaches do not know about this ...and could be helpful.

One thought that may be beneficial for your hockey athletes and parents of young hockey players. When I worked with a national championship winning inline college team at Bethel University, I observed almost all of the hockey athletes had extremely tight hamstrings. Most couldn’t touch their toes without significantly bending their knees. For a speed and strength coach, this is a priority to address quickly.

When I studied the specific movements of skating in hockey, the observation was hockey athletes rarely fully extend their knees. Unlike other sports, I would classify hockey as a sprint sport needing supreme anaerobic conditioning, and when your line is in, it’s a near all-out speed-burst sport followed by a seated rest. The speed of the game due to line rotations to keep athletes fresh makes hockey perhaps the most exciting sport of them all to watch for spectators.

When skating fast, the body is in the universal athletic position with knees and low back bent forward, and when your line is resting, athletes are seated with knees bent. This translates to tight hamstrings unless athletes are spending time several times a week working on a corrective hamstring stretching program. While hockey skating appears to be quad dominate during a forward sprint to the puck, the glutes and hamstrings are actually the primary movers propelling the body.

Whether sprinting on a track or sprint skating forward in hockey, tight hamstrings are known to restrict movement in full speed movements. Supreme flexibility however, doesn’t translate to skating faster, but strong hamstrings and glutes that are capable of full range of motion clearly improves speed. Typically, the fastest athlete on a high school football team will have the strongest and the tightest hamstrings. But when they improve flexibility, they fly, and become even faster.

Adding ten minutes of static stretching with 30-second stretch holds AFTER practice, not before, AFTER PRACTICE resulted in significant measurable improvement in just two weeks. Using the easy, self-measurement of “sit-and-reach” with knees straight initially measuring and having athletes also estimate their inches short of or passed their toes for a 3-second hold position so athletes can see their improvement, the average gain for Bethel athletes was well over 4 inches in two weeks. When athletes can physically see measurable improvement quickly, compliance increases. They are asked to self-measure their improvement at the end of every stretching routine.

Head Coach Matt Swinea bought in, and the athletes he recruited bought in to the training strategic plan that included flexibility, fast-fiber strength, and Sprint 8 during practice or in the gym to achieve supreme anaerobic conditioning (for an anerobic sprinting sport). The results speak for themselves. These were new Bethel students recruited for a brand new roller hockey team offering partial scholarships. This team won the D-1 National Championship in Salt Lake City in 2012.

We get comments from different sources. Not just here. this one is worth re-sharing.

Coach Doug writes:

Hi Greg,

Another great piece.

I’ve seen high level players who have had their careers cut short.

Our son was one of them.