TPM #279: Teaching the Inner Game

Skill development in our youth athletes must include training on how and on what to concentrate.

Welcome to edition #279. This week we look at a portion of skill development that is most often overlooked. The inner game, or mental side of sport performance. It was not taught when I was young and it not taught today . Yet, in 2024 our youth need this training more than ever.

Let’s dive in.

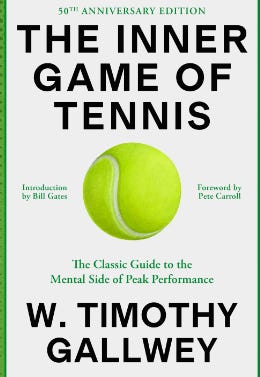

Over 50 years ago, W. Timothy Gallwey released a book call the Inner Game of Tennis.

The 1974 book is based on the realization that the key to consistent performance in tennis doesn’t lie in holding the racket just right, or positioning the feet perfectly, but rather in keeping the mind uncluttered. The lessons in the book apply to just tennis. In fact, since its release, the lessons have been credited to assisting athletes from multiple sports as well as top performers from all walks of like including politics and business. The lessons are just as relevant today as they were in 1974. Perhaps even more so when you consider there are more distractions around us today than ever.

When we look at skill development in youth sport, it follows a very specific model. Physical skill competence built through practice as well as trial and error. The mechanical. Gallwey refers to this as the “outer game”.

“The inner game” is the one played within the mind, against the hurdles of self-doubt, nervousness, and lapses in concentration.

The outer game is key for the young age groups. Those just starting need to master the ability to skate in hockey, hit the ball in baseball, pass and shoot in soccer and basketball etc. These are the foundational skills that allow for competency to be developed. Competency is the foundation for enjoying the activity.

As the skill level increases and competition is taken more seriously, athletes are subjected to increase pressure to perform. Nervousness creeps in, distractions pop up and the ability to focus on the task at hand gets compromised. We see this when expectations pop up, and when results become a focus. We especially see this when young athletes start to ‘get good’. They are relied on to perform at a high level during “pressure situations”.

Playing to the best of your ability often doesn’t happen when you’re thinking too much and generally occurs when you’re simply feeling and moving by instinct. ~ W. Timothy Gallwey

W. Timothy Gallwey describes the struggle that goes on within your mind, whether playing tennis, any sport, making a general decision, or simply trying to perform well in any aspect of your life. This is the struggle between self 1 and 2, the two sides of yourself.

Gallwey refers to Self 2 is the unconscious mind and involves the nervous system. This is the part that does the actions, e.g., the “doer.” It knows which muscles it needs to use and tense to hit the ball, and it retains that information for future use. The problem is that self 1 doesn’t trust it to do the job properly, and that is where the conflict is. Self 1 is the “teller.” This is the part that initiates the actions, e.g., it does the tensing of the muscles, it does the focusing, but this is the conscious mind, which can often trip you up during a game.

Coach Doug McKeen refers to self 1 as the front brain. The part of the brain that is trying to protect us, take the safe route. The front brain (self 1) is the part that tells us we should be able to hit the ball as it is delivered by the pitcher before we track it to the bat. In tennis, the front brain/self 1 is to blame when a juicy lob comes at us and we mis hit it. Self 1 will tell us this is an easy one and sabotage the stroke. Self 1 or the front brain is also responsible for telling us what we are doing wrong. Being hard on ourselves comes from the front brain.

We want to teach young athletes (and ourselves) how to tap into self 2. Once a skill is developed, the unconscious brain knows how to perform the skill. That is the part of the brain we want driving our actions.

When the mind is free of any thought or judgment, it is still and acts like a mirror. Then and only then can we know things as they are. ~ W. Timothy Gallwey

In many youth sports, coaches often focus on high effort, high intensity as keys to success. Without balancing that with understanding how to calm the body, the high effort can be counterproductive.

By not trying too hard, you relax your entire mind and body, often creating better results.

When an athlete is playing well, they will experience moments of authentic joy, total euphoria. This is when your mind is in harmony, with both sides working together. At this point, your mind isn’t barking instructions or telling you that you’re doing things wrong; everything is just flowing freely.

To achieve this state, athletes need to learn how to concentrate without actually putting in the effort. It should happen naturally. This involves slowing your mind down and thinking a lot less than you do now; it means avoiding judgment, and trying not to fear what you’re doing, not trying too hard, and cutting out the worry. By trying to control what you’re doing far less, you’re actually more in control than you realize! All of this occurs when your mind is in the present, firmly in the here and now.

According to Gallwey this takes time and practice. One of the exercises he suggests to practice is

• Stop reading for a second and turn your attention away

• Stop thinking

• See how long you can remain clear and thoughtless

It’s likely to be a concise amount of time at first, but the more you do it, the longer you’ll be able to remain thoughtless. It will take time because humans are programmed to think and analyze constantly. By letting go of this requirement, you’re avoiding judging yourself, being negative, and overthinking.

Mindfulness meditation is a great way to learn how to clear your mind and stay firmly in the moment. Practice for when you’re playing tennis! ~ W. Timothy Gallwey

Today, in what I call the age of distraction, our youth need to learn and practice this more than ever. To be able to not have their minds buzzing, and just be thoughtless. To focus on breathing. Finding cues that allow us to distract self 1, or the front brain, become critical in developing the inner game.

In order to play tennis to the best of your ability, you need to be able to sense and feel where the ball is, as well as listening to the ball as it hits your racket. ~ W. Timothy Gallwey

Key concepts in teaching/learning “the inner game”:

Concentration means being able to focus our attention. When we focus on one thing, our mind becomes still, it remains in the present, and it is calm. This allows you to play the game naturally and instinctively.

In order to start concentrating effectively, the focus is to be on just one thing that holds our attention;

Gallwey uses the tennis example, the best choice is the ball. Concentrate on it, watch and focus on how high it bounces, how high it travels over the net, but don’t analyze. Just watch. Become engrossed in what you’re seeing. The theory goes that when you’re concentrating on the ball and not simply watching it without focus, you’ll hit it better every single time. W. Timothy Gallwey also suggests listening to the sound the ball makes when it hits your racket, and he has found that it helps improve his game by allowing him to ‘feel’ the ball in more than one sense

We can apply this to baseball, golf and any sport where tracking the object is critical for success. The football wide receiver for example.

In sports like basketball, soccer, and hockey what is the object of focus we should be teaching?

That comes down to coaching philosophy, but most often athletes at the highest levels drill down on the steps they need to execute at a high level in order to be successful. In hockey, that could be getting to the open spaces if you are a goal scorer. It could be keeping the gaps close to opposing forwards if you are on defence. What is most important to focus on?

The ability to focus, with a calm mind is very elusive in today’s youth sport. It is not taught but needs to be.

Inner game = most fascinating game